Contradictory advice and imperfect results have made Western folk fearful of the Eastern staple of rice. Actually, says Nisha Katona, nothing could be simpler or tastier

One of my first memories is sitting on my mother's knee while she mashed rice and delicately spiced fish between her fingers on a steel plate. Quickly, she formed small balls with which to feed me. I remember the glint of the stainless steel in the Lancashire sunshine, the deftness of her fingers and the speed and the purpose with which she gently pushed the morsel past my lips. This confident haste made the interaction somewhat non-negotiable. There are not many Asian babies who require the choo-choo train spoon-into-the-tunnel routine. For so many, including myself, it is rice that is the first taste of a mother's love.

I feel a little guilty because for years, I overlooked rice as an anodyne, pasty-faced accompaniment. Why, in the West, do we treat this grain of grains like a second-cla ss citizen? Why must we dress it in garish, clownish hues to justify its presence at the Indian feast? Why does its cooking technique continue to confound adults in the West when children in the East can cook it before they can say the word?

And I am as guilty as any. To be Indian and rice phobic is like being a vegetarian Turk: hobbled where it matters most – in your kitchen. I confess that I only learnt to master rice in my thirties, when I had a young family to cook for and little time to spare. Shame on me. I work full time as well as running a busy household, so I need ingredients that will be at my beck and call – grown-up ingredients that can be shown the dressings and trusted to work their own magic. Ingredients that need not be poked and prodded and peeled and goaded into a splendid main course.

A story that changed my riceless life came from a friend who worked in Africa. There, with very limited fuel, she told me that they used one cup of rice to two of water, boiled the pan once, then placed the pan in a polystyrene box and left it to cook by itself. It did so in 20 minutes. No heat, no stirring, no straining. I became swollen with awe at this assiduous grain. I cannot think of another ingredient that requires so little, to give so much to so many.

Rice swells to three times its size when cooked. It is the staple food of more than half of the world's population. Its production alone keeps buoyant some of the world's poorest economies. Quick to cook and slow to burn, rice is patient, rice is kind, rice is not proud, rice does not boast… it is biblical in its worthiness. I became a Rice Evangelist.

But it is not just because of these merits that I wax so lyrical. It is because, quite selfishly, it allows me to cook quickly, spectacularly and deliciously with the least effort.

One-pot rice dishes are at the heart of the cuisines of the majority of the world's population. If one thinks of the crucible of rice – the kitchens of the East – this dedication makes sense. Rice cooking is favoured where fuel is precious, where pans are few, where mouths are many, where children sit on their mothers' hips as they cook one-handed.

I think many of us consider rice to be exotic, complicated, otherworldly. We think it is not our staple – our staples in the West are the potato, wheat and corn, none of which is as simple to prepare. I want to show you how to master the grain, to show you how rice is one of the hardest-working companions you can harness in your kitchen. It does not need peeling, it does not need chopping or endless preparation. It likes to be left to cook without a watchful gaze. It is eternally long-life if kept dry and airtight.

To rinse or not to rinse?

I was taught to rinse rice before cooking until the water runs almost clear. The theory goes that rinsing before cooking rice removes excess surface starch and so produces a whiter, cleaner-tasting dish. With long-grain rice this makes the final product more separate and less sticky. With sticky rice grains, it reduces – ever so slightly – the stick. Win win. I have, rather obsessively, performed numerous taste tests on this theory and concluded that, in terms of flavour, the difference is zilch. I confess, however, I always rinse rice, just as I would always wash shop-bought fruit and veg: once or twice to wash away all unbidden traces of handlers.

To soak or not to soak?

With the notable exception of a few recipes – mainly using brown rice – I rarely soak rice before cooking. But it is up to you if you have time. Soak in cold water for anything up to three hours. If you are cooking by the absorption method, cover with the measured amount of water (two cups water to one cup rice), then cook without adding any more water. For me, the beauty of rice is its humble, quick simplicity; soaking is a bridge too far. But if you feel it gives you a subtle edge and you have the time and patience, soak away.

It takes about 15 minutes for boiling water to reach the middle of a rice kernel, so while the outside has cooked for 15 minutes, the middle has been cooked for only a minute or so. And as the outside of the kernel cooks, starch leaches out, increasing stickiness. Soaking white rice for about an hour before cooking allows moisture to get to the middle of the kernel. During cooking, the heat transfers quicker to the middle and the rice will be done in about eight minutes, causing less damage to the outside of the kernel. Thus, it's more evenly cooked, and easier to separate than the non-soaked rice.

The absorption method (my favourite)

This is the method for making “steamed rice”. This method has a mindless simplicity. I discovered it when I was in my thirties – pretty late on in life for an Indian. It has never failed me.

For every one cup of rinsed rice, add two cups of water.

Simmer until the water has almost all disappeared. This usually takes about 10-15 minutes. Stir once or twice in the early stages if you must.

Then put on a tight lid, switch off the heat and wait for 15 minutes.

Do not lift the lid before this precious 15-minute period has elapsed. The sealed pan becomes the kiln of the grain and it must not be disturbed.

The straining method

This was the method I grew up with. It was a two-parent job. Mother watched the pan, summoning my father away from the news to strain the heavy, boiling vat of terror. In the East, where one eye is always fixed on the blood-sugar level, the straining method is believed best for diabetics.

Rinse the rice and add at least double the volume of water.

Boil the rice for about 20 minutes, testing the grains frequently.

When they are as soft as you want them, drain and rinse through with hot water.

Remember that the rice will continue to cook slightly once back in the pan so don't wait until it is mushy before you strain it.

The finger method

The finger method has a natural charm. There's a total absence of any measuring implements, which is logical because they rarely feature in the kitchens of the East. It is basically the same principle as the absorption method, but without the mugs.

Add as much rinsed rice as you like to any shape of pan.

Add as much water as reaches to the first joint crease on your index finger when the tip of the finger is just touching the rice.

Boil merrily until almost dry with a dimpled surface, about 20 minutes.

Switch off the heat, add a tight lid and wait for 15 minutes.

The microwave method

This is my aunt's favoured method, and she is evangelical about cooking rice in this way.

Use two cups of water for every cup of rinsed rice.

Put in a large covered dish suitable for the microwave.

Microwave in a 700w oven allowing about 15 minutes per cup of rice (or until you see that the grains are standing dry and vertical).

Remove and leave to rest for five more crucial minutes

'Pimp My Rice' By Nisha Katona (Nourish, £20) is out now.

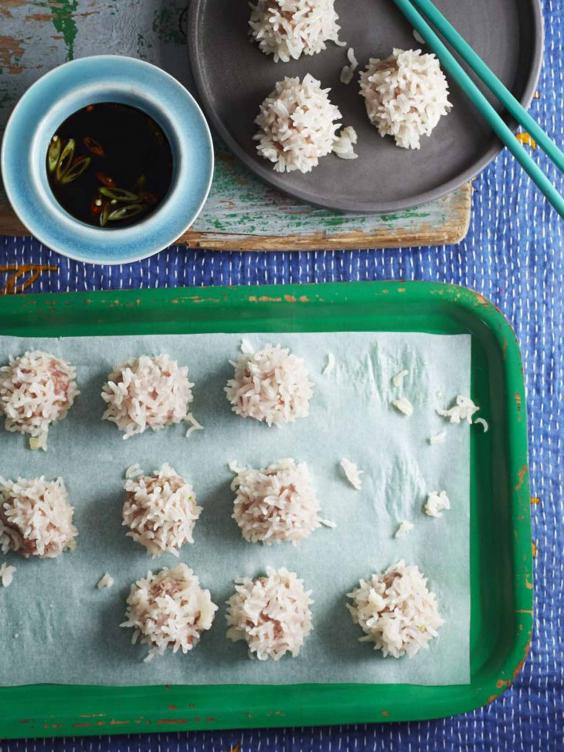

Pearly pork urchins by Nisha Katona

Serves 4

325g sticky rice

450g minced/ground pork

1 large spring onion/scallion, finely chopped

70g water chestnuts, finely chopped

1 egg white

1½ tablespoon finely chopped fresh root ginger

2 tablespoon light soy sauce

1 tablespoon Shaoxing rice wine

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon cornflour/cornstarch

1½ tablespoons toasted sesame oil

Dark soy sauce, for dipping

This simple Chinese dish always reminds me of little sea urchins. They provide a fun obstacle course for the tongue. The sticky rice grains coating the meatballs become pearly in the cooking process and stand to an enticing attention. Like the pearl, however, sticky rice needs time to develop so give it a good overnight soak before you make this dish if you can.

Soak the rice overnight. Just before you start cooking, drain it well and spread the grains out on a baking sheet.

Combine all the remaining ingredients except the sesame oil and dark soy sauce. Roll the mixture into 24 x 2cm balls and then roll each meatball in the rice so that it is coated. Put the balls on a heatproof plate about 1cm apart. You will need to do a few at a time.

Put the plate in a steamer and cook in batches. They will need to steam for around 20 minutes until they are cooked through. You are waiting for the rice to soften and for the pork to cook through. When cooked, drizzle with the sesame oil.

0 comments:

Post a Comment